- Home

- Maurice Level

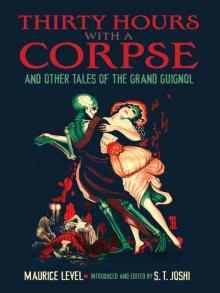

Thirty Hours with a Corpse

Thirty Hours with a Corpse Read online

DOVER HORROR CLASSICS

THIRTY HOURS

WITH A

CORPSE

AND OTHER TALES OF THE GRAND GUIGNOL

MAURICE LEVEL

INTRODUCED AND EDITED BY

S. T. JOSHI

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

MINEOLA, NEW YORK

Copyright

Copyright © 2016 by Dover Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

Thirty Hours with a Corpse and Other Tales of the Grand Guignol, first published by Dover Publications, Inc., in 2016, is a new anthology of thirtynine stories reprinted from standard sources. A new Introduction has been specially prepared for the present edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Level, Maurice, 1875–

[Short stories. English]

Thirty hours with a corpse, and other tales of the Grand Guignol / Maurice Level, introduced and edited by S. T. Joshi.

p. cm. — (Dover horror classics)

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-81099-7

1. Horror tales, French. 2. Level, Maurice, 1875– — Translations into English I. Joshi, S. T., 1958– editor. II. Title.

PQ2623.E9A2 2016

843'.912—dc23

2015031477

Manufactured in the United States by RR Donnelley

80232901 2016

www.doverpublications.com

Contents

Introduction by S. T. Joshi

The Debt Collector

The Kennel

Who?

Illusion

In the Light of the Red Lamp

A Mistake

Extenuating Circumstances

The Confession

The Test

Poussette

The Father

“For Nothing”

In the Wheat

The Beggar

Under Chloroform

The Man Who Lay Asleep

Fascination

The Bastard

That Scoundrel Miron

The Taint

The Kiss

A Maniac

The 10:50 Express

Blue Eyes

The Empty House

The Last Kiss

Under Ether

The Spirit of Alsace

At the Movies

The Little Soldier

The Great Scene

After the War

The Appalling Gift

Night and Silence

The Cripple

The Look

The Horror on the Night Express

Thirty Hours with a Corpse

She Thought of Everything

Introduction

MAURICE LEVEL (1875–1926) is the forgotten man of French literature. Although he published thirteen novels, dozens of plays, and hundreds of short stories, and was a star contributor to the celebrated Grand Guignol Theatre in Paris, Level today is virtually unknown. He does not appear in any English-language dictionaries or encyclopedias of French literature—and, incredibly, does not appear even in multivolume and presumably authoritative French encyclopedias of French literature. Not a single article has been published about him in an academic journal, and the most basic features of his life are unknown. All we have is his work.

And yet, Level enjoyed remarkable popularity in the English-speaking world during the second and third decades of the twentieth century, when two novels, The Grip of Fear (1911) and Those Who Return (1923), were translated, along with a volume of short stories, first published in England as Crises (1920) and, later that same year, in the United States as Tales of Mystery and Horror. (To add to the oddity, Level’s stories never appeared in a collection in French.) In 1921, H. P. Lovecraft, who admitted that he had not yet read any of Level’s work, wrote a paean to him based solely upon his increasing reputation:

Nay, I have never read a tale of M. Maurice’s, but have yearned to do so ever since beholding the announcement of his book of tales in the reviews a year or so ago. . . . For M. Level I have only the respect most profound—I would that I could create plots as delicious as his! How relieving it is to fly from the pitiful commonplaces of futile, trivial, superficial, ethics-mad, mockimportant, sentimental, romantic, false-idea’d, American nambypamby Sunday-school tales, to something that actually digs under the illusory surface of conventional values & feigned motives, & shakes the real fibres of the human animal!1

Lovecraft goes on here at much greater length, but this should suffice to suggest what an impression Level’s mere reputation made on an artist so sensitive to the weird, terrible, and unconventional as Lovecraft.

In “Supernatural Horror in Literature” (1927), Lovecraft’s response is somewhat more subdued. In discussing the conte cruel (“cruel tale”), “in which the wrenching of the emotions is accomplished through dramatic tantalisations, frustrations, and gruesome physical horrors,” he goes on to write: “Almost wholly devoted to this form is the living writer Maurice Level, whose very brief episodes have lent themselves so readily to theatrical adaptation in the ‘thrillers’ of the Grand Guignol.”2 The overriding fact that Level avoided the supernatural altogether in his work necessitated such a response, for Lovecraft had considerable doubts as to whether nonsupernatural horror, however “gruesome” or extreme, could ever be a legitimate branch of the “weird tale.”

As mentioned, we know next to nothing of Level’s life, except that he studied medicine for a time—a point that becomes evident in a number of his tales. It is unclear when he first became associated with the Grand Guignol Theatre, but his earliest published play appears to date to 1906. The history of the Grand Guignol Theatre has now been charted in a number of volumes,3 and from them we learn much that is of indirect interest to the study of Level and his work. The theatre was founded in 1897 by Oscar Méténier but was taken over two years later by Max Maurey. In spite of its reputation for focusing on death, madness, and eroticism, an average evening’s program at the theatre usually included a comedy. (None of the Level stories that have been translated into English are comedies except, perhaps, a single example, “The Appalling Gift.”) Otherwise, the program almost exclusively featured one-act plays, exactly of the sort suited to the intense, tightly constructed plots we find in Level’s stories. The theatre’s heyday chiefly occurred in the decade or two after World War I, but it declined in the 1930s, especially with the advent of talkies and of horror films; but it continued for decades, not shutting its doors until 1962.

Level was not the most prolific contributor to the Grand Guignol; that honor goes to André de Lorde, whose overall output includes more than 150 plays, novels, and other work. But Level’s plays were among the theatre’s biggest hits; one of them was Sous la lumière rouge (based on the story translated into English as “In the Light of the Red Lamp”), which premiered in 1911, while Le Baiser dans la nuit (based on the story “The Last Kiss”) premiered the next year. It would appear that Level wrote his stories first, publishing them in magazines and newspapers (especially the Paris paper Le Journal), then adapted them into plays, sometimes with the help of a collaborator. So far as can be ascertained, only eight of his plays were actually published. One of them, Lady Madeline (1908), is of interest in being a stage adaptation of Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

It is difficult to characterize Level’s work, save to say that its relentless emphasis on crime, hate, vengeance, and their psychological effects constitutes his distinctive contribution to literature. This is the focus of the early novel L’Épouvante (1908), translated as The Grip of Fear, although its title simply means “terror” or “fright.” In this work, a journalist, having stumbled upon a

n undetected murder, deliberately plants evidence implicating himself as the perpetrator of the crime, merely to experience the thrill of being hunted by the police. The journalist, Onesimus Coche, always imagines that he can reveal the truth to the police if matters go too far; but he finds that his emotions get the better of him as the noose tightens figuratively around his neck. He begins to crack under the strain, and it is said of him toward the end: “From the very start Coche had but one enemy: his own imagination.”

But accomplished as this novel is, Level’s reputation will probably rest on his tales, which if nothing else have all the compactness and “unity of effect” that Edgar Allan Poe believed was the signature feature of the short story. Level’s immediate literary influences in this regard were probably Guy de Maupassant (who is cited in Those Who Return) and Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, a master of the conte cruel, whose work preceded Level’s by a few decades; but these two writers themselves drew extensively upon the structural perfection of Poe’s short stories as models for their own work, and Level manifestly did so as well. Without a wasted word, Level’s tales progress from the first scene to the last in a manner that fully exhibits the conflict of emotions that is at their heart, but without the digressions and irrelevancies that often mar even the most accomplished of novels. Level’s tales reveal such an economy of means that nothing could be added to or extracted from them without destroying their very fabric.

The emphasis on terror, even if it is of an unambiguously nonsupernatural sort, makes the reading of Level’s tales at times an excruciating experience. It is not that there is any excess of physical violence involved: “The Last Kiss” is probably the most extreme in this regard, with its unflinching display of the hideous effects of acid when thrown upon a man’s (and, later, a woman’s) face. “The Kennel” is hideous in its suggestion of a corpse being fed to hungry dogs. But beyond this, the terror in Level’s tales is chiefly psychological: the terror of an impoverished prostitute being forced to service the executioner of her lover; the terror of a man coming upon definitive evidence that his lover was buried alive; the terror that a mother feels when she suspects that her newborn baby is the child of a madman. . . . Many of the scenarios Level constructs may seem somewhat contrived and artificial, but his purpose is to study the emotional extremes of those who find themselves confronted by madness, guilt, and paranoia.

There is a considerable social element in many of Level’s tales—an element that similarly links them to the Grand Guignol’s concern for naturalism, a literary movement that emphasized the plight of the outcast and impoverished and sought to display the harshness and injustice of a social fabric built upon radical inequities in wealth and social position. Many of Level’s stories feature beggars or other characters on the margins of society who plunge into crime to exact vengeance upon a society that has left them no other means of combating economic inequality. “The Beggar” is prototypical in this regard: a beggar tries in vain to bring help to a man who is being crushed by an overturned cart, but he is driven away by the man’s family because they believe he is only looking for a handout. In the end, the beggar can only express a certain wry satisfaction that the man’s own family effectively caused his death.

In tales written during and after World War I, Level cleverly adapted his blood-and-thunder style to grim and poignant narratives involving the war. His surprise endings, featuring sudden twists and unexpected dénouements, work well when applied to war scenarios. The deep resentment by the humiliated French at German occupation and brutality is searingly displayed in several tales. It would be interesting to know if any of these were adapted for the Grand Guignol.

Maurice Level remained a figure of note even after his early death. His play Le Baiser dans la nuit was performed as late as 1938 at the Grand Guignol Theatre and was even adapted (loosely and without credit) as an EC comic. But beyond the three volumes already mentioned, none of his work appeared in English in book form subsequent to 1923, and only a few scattered tales appeared in English-language magazines in the later 1920s and 1930s. (Three of them appeared in the celebrated American pulp magazine Weird Tales.) But among devotees of psychological suspense and the macabre, Level’s work has always retained a shadowy interest, and he has refused to fade away. The present volume, which contains virtually every short story by Level that has been translated into English, should confirm that that interest is well deserved. Few authors have displayed greater psychological acuity, greater craftsmanship in the manufacture of short stories, and a more unflinching gaze at the grotesque crimes that human passions are capable of engendering; and few have exhibited those crimes and those passions with loftier artistry.

—S. T. JOSHI

A Note on the Texts

This volume reprints, with a single exception, all the short stories by Level that have been translated into English. The first twenty-six stories are taken from Crises (1920). The next six stories are taken from Tales of Wartime France, translated by William L. McPherson (1918). The last seven stories are uncollected tales appearing in magazines. They are: “The Appalling Gift” (Living Age, 24 March 1923); “Night and Silence” (Weird Tales, February 1932); “The Cripple” (Weird Tales, February 1933); “The Look” (Weird Tales, March 1933); “The Horror on the Night Express” (Mystery Magazine, February 1934); “Thirty Hours with a Corpse” (Mystery Magazine, September 1934); and “She Thought of Everything” (Mystery Magazine, May 1935). No translators were given for any of these stories.

The one story by Level that has not been included here is “The Old Maids,” published in Jacqueline and Four Other Stories from the French [no translator indicated] (1925). It is a fine tale (a translation of “Vieilles Filles”), but so obviously a mainstream story that its inclusion could not be justified here.

Where practicable, the translations have been revised by consultation with the original French texts.

—S. T. J.

* * *

1 H. P. Lovecraft to Myrta Alice Little (17 May 1921); Lovecraft Studies No. 26 (Spring 1992): 28–29.

2 The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature, ed. S. T. Joshi (New York: Hippocampus Press, 2012), p. 53.

3 See Mel Gordon, The Grand Guignol: Theatre of Fear and Terror (New York: Amok Press, 1988); Richard J. Hand and Michael Wilson, Grand-Guignol: The French Theatre of Horror (Exeter, UK: University of Exeter Press, 2002). The latter volume contains new translations of Level’s Sous la lumière rouge (as In the Darkroom) and Le Baiser dans la nuit (as The Final Kiss).

The Debt Collector

RAVENOT, DEBT collector to the same bank for ten years, was a model employee. Never had there been the least cause to find fault with him. Never had the slightest error been detected in his books.

Living alone, carefully avoiding new acquaintances, keeping out of cafés and without love-affairs, he seemed happy, quite content with his lot. If it were sometimes said in his hearing: “It must be a temptation to handle such large sums!” he would quietly reply: “Why? Money that doesn’t belong to you is not money.”

In the locality in which he lived he was looked upon as a paragon, his advice sought after and taken.

On the evening of one collecting day he did not return to his home. The idea of dishonesty never even suggested itself to those who knew him. Possibly a crime had been committed. The police traced his movements during the day. He had presented his bills punctually, and had collected his last sum near the Montrouge Gate about seven o’clock. At the time he had over two hundred thousand francs in his possession. Further than that all trace of him was lost. They scoured the neighborhood and waste ground that lies near the fortifications; the hovels that are found here and there in the military zone were ransacked: all with no result. As a matter of form they telegraphed in every direction, to every frontier station. But the directors of the bank, as well as the police, had little doubt that someone had lain in wait for him, robbed him, and thrown him into the river. Basing their deductions on certain clues, they were able

to state almost positively that the coup had been planned for some time by professional thieves.

Only one man in Paris shrugged his shoulders when he read about it in the papers; that man was Ravenot.

Just at the time when the keenest sleuth-hounds of the police were losing his scent, he had reached the Seine by the Boulevards Exterieurs. He had dressed himself under the arch of a bridge in some everyday clothes he had left there the night before, had put the two hundred thousand francs in his pocket, and making a bundle of his uniform and satchel, he had dropped the whole, weighted with a large stone, into the river and, unperturbed, had returned to Paris. He slept at a hotel, and slept well. In a few hours he had become a consummate thief.

Profiting by his start, he might have taken a train across the frontier, but he was too wise to suppose that a few hundred kilometers would put him beyond the reach of the gendarmes, and he had no illusions as to the fate that awaited him. He would most assuredly be arrested. Besides, his plan was a very different one.

When daylight came, he enclosed the two hundred thousand francs in an envelope, sealed it with five seals, and went to a lawyer.

“Monsieur,” said he, “this is why I have come to you. In this envelope I have some securities, papers that I want to leave in safety. I am going for a long journey, and I don’t know when I shall return. I should like to leave this packet with you. I suppose you have no objection to my doing so?”

“None whatever. I’ll give you a receipt . . .”

He assented, then began to think. A receipt? Where could he put it? To whom entrust it? If he kept it on his person, he would certainly lose his deposit. He hesitated, not having foreseen this complication. Then he said easily:

“I am alone in the world without relations and friends. The journey I intend making is not without danger. I should run the risk of losing the receipt, or it might be destroyed. Would it not be possible for you to take possession of the packet and place it in safety among your documents, and when I return I should merely have to tell you, or your successor, my name?”

Thirty Hours with a Corpse

Thirty Hours with a Corpse